Image via WikipediaThe current issue of ARTnews includes an article that reframes Picasso, as contemporary artists understand his work. Anyone who's seen a few knows that he likes to paint women, many of which appear to be disfigured and reimagined. What emerges when the standards of art-making have been further replicated and challenged over time? ARTnews' writer Ann Landi posed these questions:

Image via WikipediaThe current issue of ARTnews includes an article that reframes Picasso, as contemporary artists understand his work. Anyone who's seen a few knows that he likes to paint women, many of which appear to be disfigured and reimagined. What emerges when the standards of art-making have been further replicated and challenged over time? ARTnews' writer Ann Landi posed these questions:But what about contemporary artists—the young and those in midcareer? Does Picasso still cast any sort of spell, almost 40 years after his death?Good questions! As an undergraduate student, the myth of Picasso became solidified through an unexpected source -- Fernande Olivier, one of his early (cough) lovers (I never use that word but it seems most appropriate in this context). Her relationship with Picasso was vividly illustrated, in her own words, throughout her journals. Loving Picasso: The Private Journal of Fernande Olivier is totally worth a read. After the demise of their relationship, of course, Picasso's Fernande Olivier's portraits ceased.

What I understood about his ever-evolving themes, and his relationship with Olivier, was this: while it's true that Picasso was a master at his craft, he may not have ever mastered any of his favorite subject matter (namely, women). What I see in his famously fragmented portraits of women such as Dora Maar (top image) and Fernande Olivier is more of a struggle to understand -- this is what makes it interesting today. We still can't place the emotion or the true connection to Picasso. It's clearly not a matter of simple objectification, and the women are transformed into monumental ghosts. Look at these examples of his portraits of women in his life, and note their monolithic appearances:

Image by wallyg via Flickr

Image by ahisgett via Flickr

Image by ahisgett via FlickrWhat I would ask is related and more specific: What are the portraits of women translating into now? For British-born artist Nicola Tyson, the answer was simultaneously unfulfilling and inspiring. Landi observed Nicola's response in her article, and explained that,

Though her debt to him is more oblique now, Tyson, who also shows at Friedrich Petzel, concedes that Picasso is the one who "gave permission way back to represent the figure differently from the traditional academic form." His depictions of "vacant women," she adds, "worked as a spur for me toward more self-discovery—out of a kind of anger and a feeling that there was something lacking in his work, something that wasn't represented."

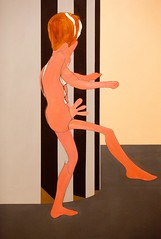

Below are images that embody Tyson's approach to her subject matter, which is also largely concerned with the human form and psychological undertones:

Image by Strifu via Flickr

Image by Strifu via Flickr

I still like Picasso. Sometimes I imagine that such intense relationships, in which he portrayed his partners constantly, involved a great sense of exploration, which is always good for all parties involved. After reading Fernande Olivier's journal, Picasso seemed less like a monster and more like anyone else who might fall in love and lose control. Consequently, the women in his portraits are always admirably comfortable in their (somewhat questionable) positions.

The article left me thinking about how much I absorbed, and tried out (like Picasso's obsessive need to change styles), in my search for a greater understanding of my own vernacular. For me, it was family and love, which is not too far off from Picasso's oeuvre. Did Picasso (or other "great masters") help you to accept or reject anything in particular about art-making, and if so, do you still like this artist? Or did you outgrow them?