International Women’s Day, a 104-year old tradition, honoring women’s social, economic, and political achievements and calling for greater equality and recognition of women’s rights. Its history dates back to the suffragette movement in the United States, when women took to the podiums and the streets, demanding the right to vote.

You may remember that my first post for Her Blueprint, The Power of Voice, shared my experience introducing a public speaking training, grounded in the right to self-expression, to a group of Maasai and Kalenjin women in Kenya — and the transformative effect such training had on them and their community. I'm aware of few development organizations that train rural women in public speaking. So in my own small way, I advocate for public speaking training for rural women in developing countries every chance I get.

Imagine my excitement, while recently conducting a gender analysis in Malawi, when I happened upon a tool, the Women's Empowerment in Agriculture Index, which, among other factors, measures women’s comfort in public speaking as a key contributor to women's empowerment.

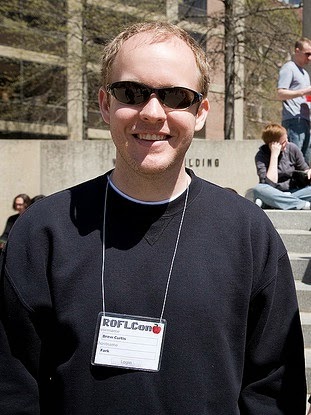

|

| Roda from Narok County, Kenya practices her public speaking skills. Photo: Landesa/Deborah Espinosa |

Launched by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, and USAID's Feed the Future Initiative, the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index is the first standardized tool to comprehensively measure women’s empowerment and inclusion in agriculture.

Among other constraints, women’s comfort in public speaking is measured along with group membership under the “Community Leadership” domain. “Group membership is an important source of social capital, and this indicator measures whether a woman is a member of at least one group out of a wide range of social and economic organizations.”1 High rates of disempowerment in the Community Leadership domain may indicate social and cultural norms that discourage participation in activities outside the home.2

Among the countries included in the Index Baseline Report, discomfort in public speaking was among the top three greatest contributors to women’s disempowerment in 3 out of 13 countries: Bangladesh, Malawi, and Zambia. For all 13 countries, constraints in the Community Leadership domain, generally, comprise from 14% (Liberia) to 37% (Nepal) of all constraints contributing to women's disempowerment.

Given the significant other domains that the WEAI measures, i.e., production decision-making, access to productive resources, control over use of income, and time allocation, I am excited that I now have support for asserting the importance of women's leadership in communities, including group membership and feeling comfortable speaking in public to women's empowerment.

So for all of you international development practitioners out there, how do we honor this year's International Women's Day theme of "Make it Happen?" How does your program or project support women in gaining confidence to speak in public? To share their stories? To advocate for their rights?

There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.~ Maya Angelou

1 Measuring Progress Toward Empowerment: Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index: Baseline Report (2012).

2 Id.

.JPG)